As it is, As it was, As it could be

Photographer Steven Evans’ elegaic portrait of a forsaken Icon

by Aria Novosedlik

The Portuguese have a word for it: ‘saudade’.

Derived from the Latin word for solitude, ‘saudade’ refers to a sense of profound nostalgia, a wistful longing for something that no longer exists– or perhaps never quite did. It invokes a kind of melancholia.

‘Saudade’ is how you feel while leafing through renowned architectural photographer Steven Evans’ latest book, ‘As it is - A precarious moment in the life of Ontario Place’.

West entrance to the Ontario Place cinesphere and pods. | ©Steven Evans

Like any great documentarian, Evans takes particular care to capture the semi-abandoned grounds of Ontario Place (OP) as objectively as possible, avoiding the temptation to sentimentalize or stylize. In this context, ‘as it is’ carries a double meaning. First as the visual record of a moment in time, untainted by self-expression, and second as a plea to refrain from disturbing the OP site and leaving it ‘as it is’.

Despite Evans’ visual restraint, the sheer state of decay still elicits mourning for a place that once embodied hope for a bright future.

Graffiti covers the bottom of the observation tower. | ©Steven Evans

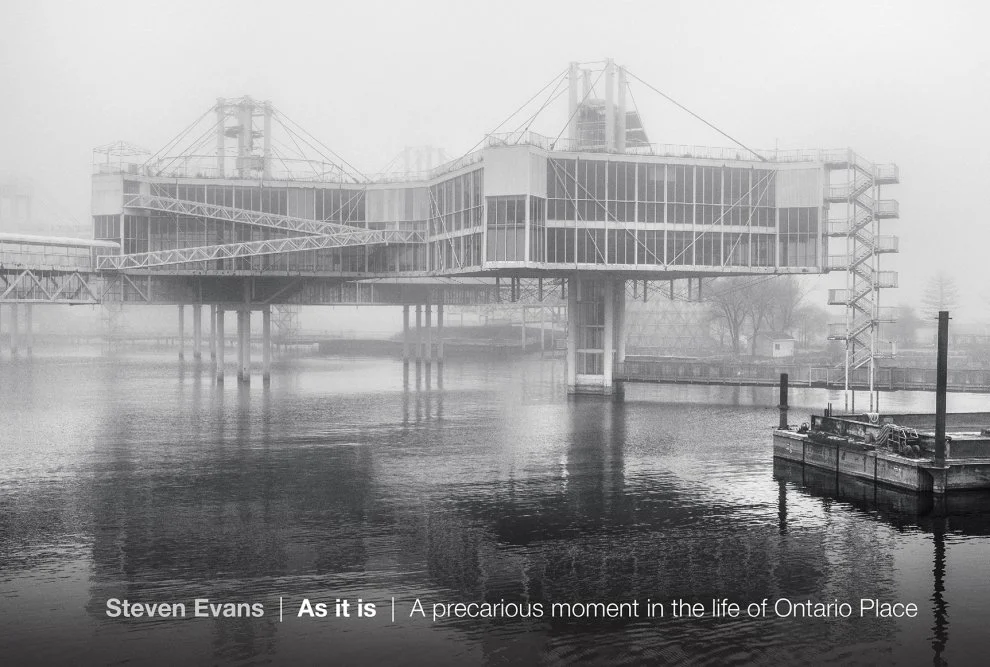

The cover of ‘As it Is’ perfectly captures this lost opportunity with a shot of the visionary architectural pods suspended over Lake Ontario like ghosts on stilts, veiled in thick fog.

The book’s cover presents a moody view of Eberhard Zeidler’s glazed pods. | ©Steven Evans

The book is prefaced with essays written by Evans, award-winning journalist John Lorinc and the esteemed Art Gallery of Ontario’s curator of photography, Maia-Mari Sutnik. Lorinc focuses on the importance of placemaking and the creation of Ontario Place, while Sutnik considers Evans’ work within the context of photographic history.

Underside of the west entrance bridge. | ©Steven Evans

Evans’ interest in the quietly rusting mass of this once visionary and still iconic architecture can be attributed to pandemic isolation and the paucity of outdoor space in downtown Toronto in which to escape it. He recalls two other distinct interactions with OP: when he was a teenager in the 70s desperately seeking a place to hang out with his friends sans-parental supervision, and when he was a young father in the nineties who needed a place to entertain his kids in the summer.

The structure of the book mirrors my own post-pandemic meanderings through OP’s west island as I tried to remember what this overgrown piece of land was like back in my childhood. Evans makes it clear that this seemingly random, labyrinthine design serves a purpose: it encourages exploration. The land is inviting you to get lost, slow down and slip away from the demands of city life.

Open air event space, originally designed as a lookout and later used as a helipad. | ©Steven Evans

The book is organized into six chapters, representing distinct sections of OP’s grounds, explaining their individual historical backgrounds, highlights, and heydays. As Lorinc’s essay points out, the first section, devoted to the west entrance comprising the Buckminster Fuller-inspired cinesphere and the pods, highlights two different inspirations: New York’s 1964 World’s fair and Montreal’s Expo 67, which both acted as catalysts for the development of Ontario Place.

View of silos, decommissioned flume adventure ride and now-empty manmade lake. | ©Steven Evans

Photos of the silos that once housed theme park rides show them poking out of the undergrowth, enveloped by what has become a forest. They are divided by the eerie, now vandalized flume ride that once hugged the west island’s curves. Some of these photos are reminiscent of those taken at Chernobyl’s post-nuclear Pripyat theme park, now crumbling in the half-life of its radioactive senescence. While not nearly as disturbing, there’s a poignancy in these images of OP, a place once overrun by joyful children, now a victim of neglect and bureaucratic ineptitude.

The dilapidated, post-nuclear ferris wheel at Pripyat Park, Chernobyl, Ukraine. | ©www.modlar.com

The last half of the book includes views of the east island’s recently revived Trillium Park. This offers a glimpse into how much potential the entire site has. With its manicured gardens, public fire pits, trails along the water, and sweeping views of the downtown skyline, Trillium Park is a welcome respite from Toronto’s urban density. Shots of the Indigenous residential school monument remind us that this land was once inhabited by a people whose way of life was completely uncontaminated by the extractive ethos of late capitalism. This land was meant to be shared, not hastily handed off to private entities at the expense of the public purse.

Ceremonial firepit, a design element suggested by Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. | ©Steven Evans

It's right and proper to castigate the Ford government for its partnership with Therme. It’s highly doubtful that taxpayers are eager to foot Therme’s $650 million bill for a 5-level, 2100-car underground parking lot, the profits from which will enrich Therme and the carbon emissions from which will pollute Ontario for the next 95 years.

Looking at the lagoon and the natural stone and vegetation of Michael Hough’s landscape design | ©Steven Evans

As politically galvanizing and rage-inducing as this situation is, Evans’ lens remains neutral. He masterfully avoids inserting his own political biases into the subject matter while still allowing his skill and expertise to shine through. It’s a fine balance. When speaking with him, he makes it clear that the project is a means for us to really examine OP and contemplate the best use for such a rare piece of manmade nature.

As Maia-Mari Sutnik writes, “These images raise awareness and draw attention to notable public spaces that have evolved out of a sense of the public good, an empathy for social needs and a philosophy of mutual spirit as the collective agency for common purpose. Evans’ project demonstrates the legacy of a past gone awry and suggests the possibility of preserving and conserving this natural environment for the public.”

It’s unlikely the Ford government will scrap its plans to destroy this pristine public space, starting with the removal of 1556 mature trees and the plowing under of the cleanest beach on the waterfront. If nothing else, Evans’ ‘As it is’ will become as it was – an important historical snapshot of the moment in which we lost what could have been.

All images of Ontario Place are ©Steven Evans and may not be reproduced without consent. Images were shot with a Canon 5D Mark 4 and a FUJIFILM XV100 point-and-shoot camera. Text by Aria Novosedlik | edited by Will Novosedlik

Book design: Bhandari & Plater