A Brief History of Simplicity

Lao Tzu: man of few words.

………….........................................................................

Originally published in Misc Magazine, 2013

………….........................................................................

3 MINUTE READ

As an idea, simplicity has a long history. The earliest mention of it can be found in The Way of Lao-Tzu (604-531 BCE): “Manifest plainness. Embrace simplicity.” But its brevity was short-lived.

Aristotle: man of more words.

A couple hundred years later, on the other side of the globe, Aristotle (384-322 BCE), said of it, “We may assume the superiority ceteris paribus of the demonstration which derives from fewer postulates or hypotheses.” In other words, simpler ideas are better ideas. Clearly he hadn’t read Lao-Tzu, or he might have thought of a simpler way to say it.

Ptolemy: unnecessarily polite

The great Graeco-Roman-Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy (367-283 BCE), whose life overlapped that of Aristotle, came to a very similar conclusion, but stated it somewhat more elegantly: “We consider it a good principle to explain phenomena by the simplest hypothesis possible". Politely said, but the first half is unnecessary. Coulda started with "explain".

Thomas Aquinas: God likes things simple

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), wrote, "If a thing can be done adequately by means of one, it is superfluous to do it by means of several; for we observe that nature does not employ two instruments if one suffices.” (Thomas, you had me at ‘several’). Somewhat more parsimoniously, Aquinas is also credited with saying that “God is infinitely simple”, thus equating simplicity with divinity.

William of Ockham: the closest shave of all

The next one to come along, and this is the most famous, was made by another 13th century monk named William of Ockham (1287-1347 AD): “Plurality must never be posited without necessity”. It is referred to as ‘Ockham’s Razor’ for its refreshing brevity and its implicit exhortation to shave away any information that is unnecessary in getting an idea across. But it ain't Lao Tzu.

Galileo: "What Ptolemy said."

Then there was Galileo (1564-1642), who in the course of making a detailed comparison of the Ptolemaic and Copernican models of the solar system, said “Nature does not multiply things unnecessarily”. He must have plucked that right out of Ptolemy’s playbook, managing to restrain himself from embellishing it in any way.

Sir Isaac Newton: superfluous pomposity. I mean, just look at his hair.

The year of Galileo’s death saw the birth of the next important figure to weigh in on the subject: none other than Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727). “Nature is pleased with simplicity, and affects not the pomp of superfluous causes”, he said pompously. (How could nature possibly affect pomp?). Newton reiterates this as one of his three ‘Rules of Reasoning in Philosophy’ at the beginning of Book III of Principia Mathematica: “We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.” Did he talk like that at the pub?

Immanuel Kant: the voice of pure reason

Philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), in his Critique of Pure Reason, reprises Ockham with the words “rudiments or principles must not be unnecessarily multiplied” and argues that this is a regulative idea of pure reason which underlies scientists' theorizing about nature.

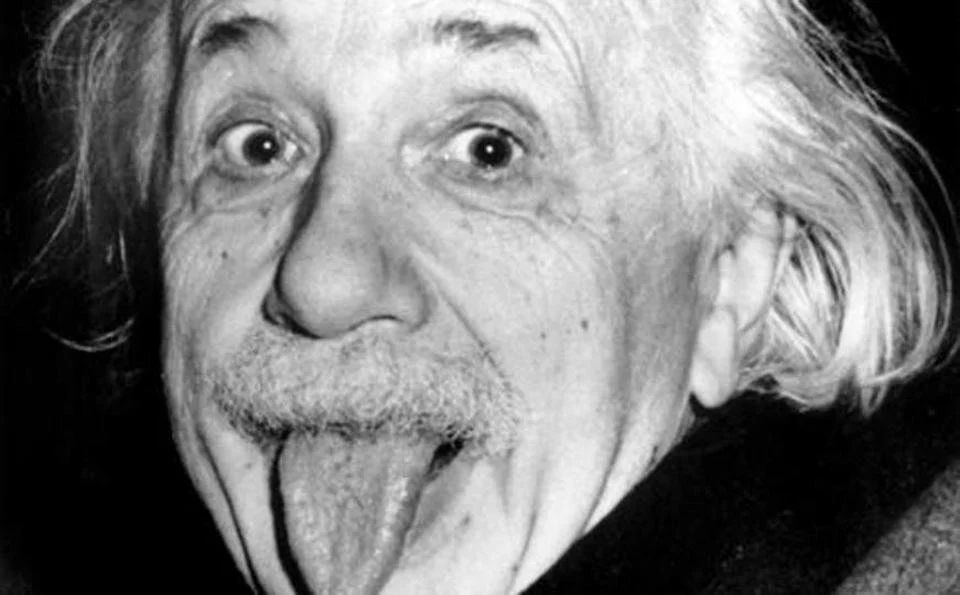

Albert Einstein: getting closer. Relatively speaking.

One hundred and fifty years later, Albert Einstein (1879-1955) is credited with this observation:

“The grand aim of all science…is to cover the greatest possible number of empirical facts by logical deductions from the smallest possible number of hypotheses or axioms.” He also said “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not one bit simpler.” Had he said the second one first, the first one would have been unnecessary.

Despite its demonstrably long lineage, the shortest reiteration of this idea was not coined until the 20th century, and not by a philosopher, theologian or scientist, but by a designer: Mies van der Rohe. He did it in three monosyllables: “Less is more”.

Mies van der Rohe: The winner!

It took 2500 years to bring it back to where Lao-Tzu had it, which begs the question, why so long? In the history of philosophy, you can read for yourself just how convoluted and complicated the debate about simplicity can get. I got lost somewhere between syntactic simplicity (the number and complexity of hypotheses) and ontological simplicity (the number and complexity of things postulated).

Philosophy gets quite bogged down in questions about the difference between these two ‘kinds’ of simplicity, and can’t seem to address the idea without complicating it with statements like “reducing the ontology of a theory may only be possible at the price of making it syntactically more complex” or, “Ockham’s Razor implies that—other things being equal—it is rational to prefer theories which commit us to smaller ontologies”.

If the philosophical debate on simplicity was lunch, it would be a Dagwood sandwich. Between the plain white bread of Lao-Tzu at the bottom and Mies van der Rohe at the top, the long middle is a complicated pile of mystery meat and convoluted condiments, inter-leafed here with metaphysical sauce, there with rational sauce, and served with a big helping of obscure language. What’s missing is simplicity.